A History of Making

The concept of Making is not a new one because “people have been making things forever” (Halverson & Sheridan, 2014, p. 495). As far back as the Stone Age, people used materials in their environment to Make tools to solve problems as they encountered them (Malafouris, 2013). The arts and crafts movement (text and video explanations), project-based learning, design-based learning, and DIY, among others, are all considered related to Making because they “share the spirit of self-produced and original projects” (Halverson & Peppler, 2018, p. 286).

The widespread adoption and expansion of today’s Maker movement was facilitated by the decentralization (ease of access and low-cost technology) of digital technologies such as digital art, programming languages, science, computers, 3-D printing, etc. Moreover, the launch of Make:Magazine in 2005, and the Maker Faire one year later, brought together artists, builders, and admirers of the Maker Movement, and further catalyzed the Maker Movement.

Today, the act of Making – or designing, building, and innovating with tools and materials to solve practical problems (Halverson & Sheridan, 2014) – invites people to express themselves and share their creations, ideas and designs. Thus, the Maker movement has been widely embraced in communities, schools, libraries, museums, and with our project, the mathematics teacher education program at Montclair State University.

The Making of things has been widely used in education as a venue for the development of students’ STEM proficiencies.

Maker History at

Montclair State University

Montclair State University has its own history with supporting teachers in “making” objects for learning. In 1975, at what was then called Montclair State College, Professors Evan Maletsky and Max Sobel published their “Teaching Mathematics: A Sourcebook for Aids, Activities, and Strategies” (link). In their book, Maletsky and Sobel highlighted how “the art of teaching” could be motivated by “a discussion of activities, materials, and manipulatives suitable for classroom use in individual or class instruction” (p. ix). As part of this mission, the authors provide ideas to teachers on how to “make” manipulatives for teaching and learning mathematics. Meet Evan and Max below and then engage with a sample of their suggestions!

Montclair State University has its own history with supporting teachers in “making” objects for learning. In 1975, at what was then called Montclair State College, Professors Evan Maletsky and Max Sobel published their “Teaching Mathematics: A Sourcebook for Aids, Activities, and Strategies” (link). In their book, Maletsky and Sobel highlighted how “the art of teaching” could be motivated by “a discussion of activities, materials, and manipulatives suitable for classroom use in individual or class instruction” (p. ix). As part of this mission, the authors provide ideas to teachers on how to “make” manipulatives for teaching and learning mathematics. Meet Evan and Max below and then engage with a sample of their suggestions!

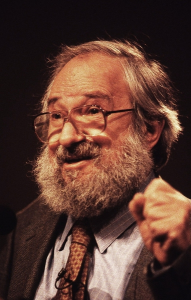

Evan Maletsky

Professor Evan Maletsky was an instrumental contributor to the Maker movement and broader mathematics education community. He received a Lifetime Achievement Award in 2009 from the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM) for his important work in the field. Please visit Evan’s NCTM Lifetime Achievement Award page for more details on his amazing contributions, or check out some examples (below) of the work he did with Professor Max Sobel in helping teachers Make meaningful, shareable, mathematical objects.

Professor Evan Maletsky was an instrumental contributor to the Maker movement and broader mathematics education community. He received a Lifetime Achievement Award in 2009 from the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM) for his important work in the field. Please visit Evan’s NCTM Lifetime Achievement Award page for more details on his amazing contributions, or check out some examples (below) of the work he did with Professor Max Sobel in helping teachers Make meaningful, shareable, mathematical objects.

Max Sobel

Professor Max Sobel worked closely with Evan Maletsky at Montclair University to further the Maker movement and support teachers in their own Making of mathematical manipulatives and shareable objects. Max receieved a Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics in 1998. You can engage with some of his and Evan’s meaningful contributions to Making and mathematics education by checking out the examples from their book (below), as well as visiting Max’s NCTM Lifetime Achievement Award page.

Professor Max Sobel worked closely with Evan Maletsky at Montclair University to further the Maker movement and support teachers in their own Making of mathematical manipulatives and shareable objects. Max receieved a Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics in 1998. You can engage with some of his and Evan’s meaningful contributions to Making and mathematics education by checking out the examples from their book (below), as well as visiting Max’s NCTM Lifetime Achievement Award page.

Some of Evan and Max's Ideas

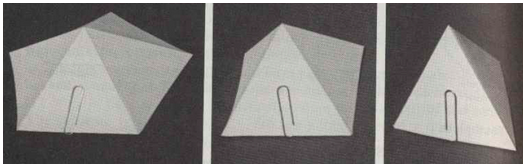

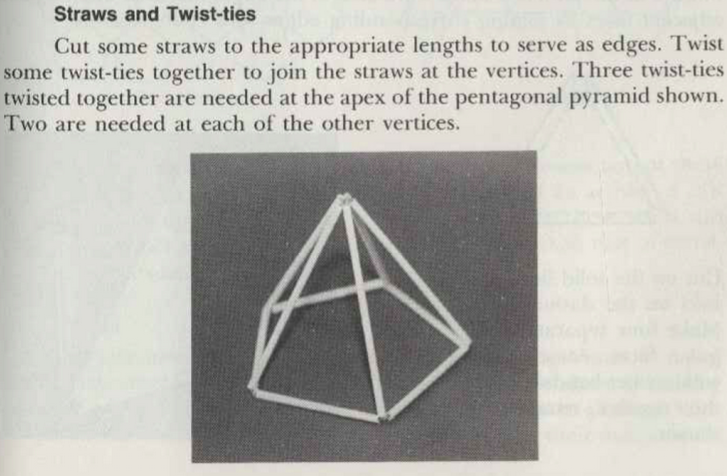

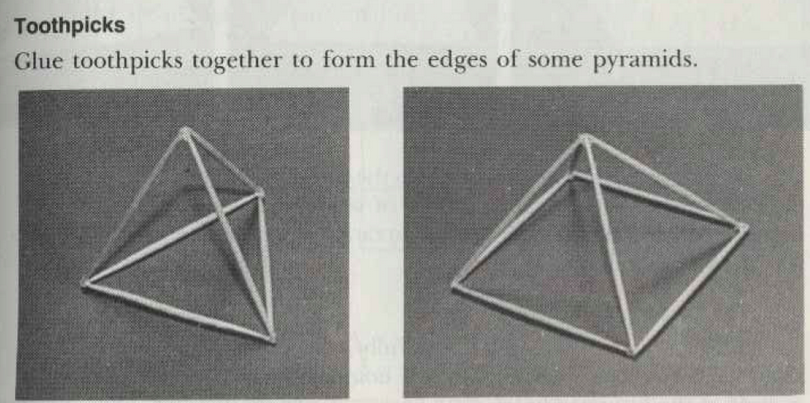

Making Pyramids with Cardboard, Straws, and Toothpicks

To help students explore relationships for pyramids’ vertices and edges, Maletsky and Sobel suggest cutting regular hexagons from heavy cardboard and folding along their three main diagonals. “As you curl up the hexagon, models of a pentagonal, square and triangular pyramid are formed. A paper clip can be used to hold the pyramid in place.” (p. 208). Toothpicks, straws and twist-ties can also be used. Try to discover how a pyramid with an n-gon for its base has n + 1 vertices and 2n edges!

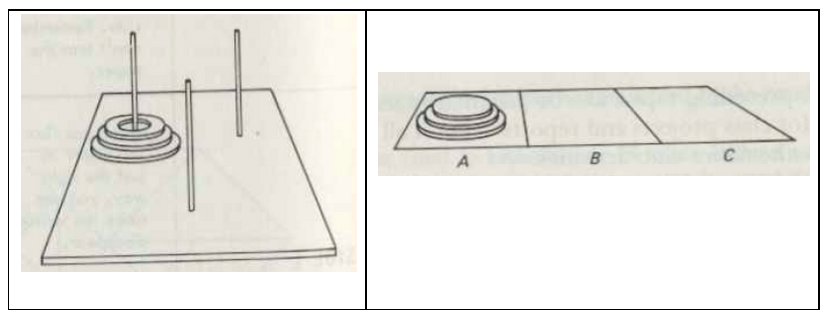

Making the Tower of Hanoi: Two Possibilities!

The Tower of Hanoi is a famous mathematical puzzle usually played on a wooden or plastic stand with three inserted pegs, and three movable disks of different sizes. The object of the game is to move the disks to a different peg using the fewest possible moves under the following conditions:

(1) Move only one disk at a time,

(2) No disk may be placed on top of one smaller than itself.

If you cannot construct the stand, Sobel and Maletsky suggest dividing a cardboard into three sections (the “pegs”) and using a penny, nickel and quarter as the disks. Try to reproduce the displayed arrangement of disks below on another peg to solve the puzzle!

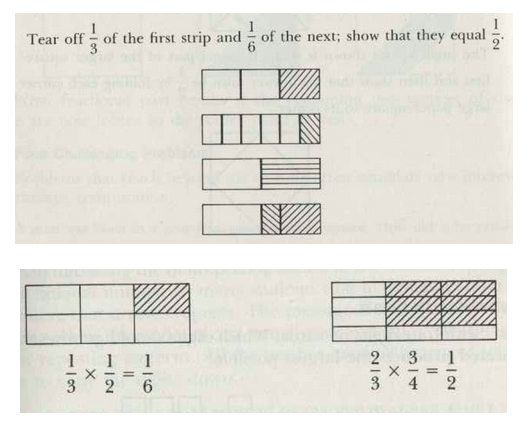

Making Your Own Fraction Strips

Anticipating the utility and significance of fraction strips, Maletsky and Sobel suggest folding like-sized, rectangular strips of paper into parts to add and subtract fractions. They also fold rectangular strips to demonstrate area models for multiplying fractions. Try some other addition, subtraction and multiplication problems with the strips!

Other Notable Contributors to the Maker Movement

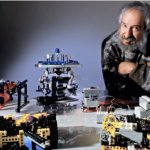

Seymour Papert

Seymour Papert developed a theory of learning called constructionism, which is based upon Piaget’s constructivism. Both constructivism and constructionism recognize that knowledge is actively constructed by a learner, with constructionism adding the dimension that the knowledge be constructed during the process of making a shareable object (Harel & Papert, 1991). Constructionism posits that people learn effectively through Making things and recognizes children as the designers and builders of their own cognitive tools. And by Makers sharing their designs, the practice of Making helps enhance and extends conceptual understandings of critical socio-technical issues.

Seymour Papert developed a theory of learning called constructionism, which is based upon Piaget’s constructivism. Both constructivism and constructionism recognize that knowledge is actively constructed by a learner, with constructionism adding the dimension that the knowledge be constructed during the process of making a shareable object (Harel & Papert, 1991). Constructionism posits that people learn effectively through Making things and recognizes children as the designers and builders of their own cognitive tools. And by Makers sharing their designs, the practice of Making helps enhance and extends conceptual understandings of critical socio-technical issues.

Read more about Papert’s important book, Mindstorms.

1969 – The Logo Turtle – Seymour Papert et al (South African/American). (2015, August 24).

Yasmin Kafai

Yasmin Kafai was born in Germany and has studied and worked in Germany, the USA, and France. She is a Professor of Learning Sciences at the University of Pennsylvania. Kafai worked with Seymour Papert at the MIT lab. Bringing constructionist perspectives to computer programming, Kafai has engaged in designing and researching online tools, projects, and communities with the aim of promoting computational making, crafting, and creativity. She helped develop the Scratch programming language that millions of kids are using to program interactive stories, games, and animations. She has authored or co-authored many books, including Connected Code: Children as the Programmers, Designers, and Makers of the 21st century, which examines the downfall and comeback of programming, and connects coding to design. Her other book, Connected Gaming, focuses on constructionist approaches to gaming and learning.

Yasmin Kafai was born in Germany and has studied and worked in Germany, the USA, and France. She is a Professor of Learning Sciences at the University of Pennsylvania. Kafai worked with Seymour Papert at the MIT lab. Bringing constructionist perspectives to computer programming, Kafai has engaged in designing and researching online tools, projects, and communities with the aim of promoting computational making, crafting, and creativity. She helped develop the Scratch programming language that millions of kids are using to program interactive stories, games, and animations. She has authored or co-authored many books, including Connected Code: Children as the Programmers, Designers, and Makers of the 21st century, which examines the downfall and comeback of programming, and connects coding to design. Her other book, Connected Gaming, focuses on constructionist approaches to gaming and learning.

Read more about Kafai’s Learning Design by Making Games.