LEARN FROM OUR MAKERS

Here we present the actual experiences and reflections of three students who participated in our Maker project. Their work demonstrates the value of Making in the teaching and learning of mathematics and why you should try it!!

Jessica and Maya's No Más Caídas

"Our shared image of No Más Caídas’s simplicity and ease of use is an expression of our desires as current (Maya) and future (Zoe) teachers in making math accessible, active, and embodied to everyone."

HOW THEY STARTED

Maya and Jessica sought to create a tool for counting. At first, Maya was resistant to explore what her rich cultural background could offer the design process, deeming it irrelevant as she brought with her the limiting yet familiar disconnect between out-of-school knowing and in-school learning. But Maya’s partner on the project, Jessica, continued to encourage her to leverage and share her experience learning mathematics from her childhood in the Dominican Republic as they navigated the various design decisions they faced during the Making process.

WHAT THEY MADE

Having grounded their project in a particularly meaningful social, cultural, and historical context, Jessica and Maya intended for the final design of No Más Caídas to embody how children across countries and cultures “do math” when engaged in “counting as playing.” The Makers drew on the mathematical activities of children in the Dominican Republic engaged in counting games like quien trajo más (who brought more) and el que dice _____ sale! (“whoever says ____ is out!”, a counting game where a child who says the pre-selected number is out). In the spirit of such games, No Más Caídas aims to provide its users with an invitation to count with concrete objects by sliding, watching, and hearing marbles fall down a 3-foot-tall tower.

WHAT THEY SAID

“Constructing our particular math tool as a way of removing the worry around losing track of these [objects or marbles] gave us something to create that had meaning for both of us and for our students. Our shared image of No Más Caídas’s simplicity and ease of use is an expression of our desires as current (Maya) and future (Jessica) teachers in making math accessible, active, and embodied to everyone. We chose marbles as the objects to be counted as a symbolic token of Maya’s country, the Dominican Republic, and her childhood experiences there.”

For more, Click here (PDF)

WHAT THIS TELLS US

Our project highlights the possibilities of creating a teacher education environment where students are able to support each other in articulating their cultural stories and lived histories.

David's Prisms with Mismatched Holes

HOW HE STARTED

David was student-teaching in a kindergarten class and brought a lived history with caring teachers to the course. David initially decided to work on re-creating an already-existing manipulative with a fellow PMT in the course. He submitted his first video interview with “Vincent,” a student with Autism Spectrum Disorder from his kindergarten class. Upon watching the video, the TE was struck by David and Vincent’s warm interactions and careful calibrations of each other’s movements on the classroom floor and suggested to David the idea of designing a new manipulative centered on Vincent. David opens to accepting responsibility for Vincent’s care, sharing and utilizing Vincent’s knowledge and love of diverse shapes to pose a second design idea of regular polygons for Vincent to tessellate.

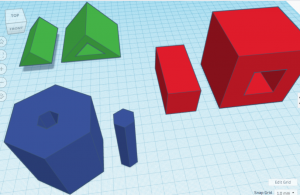

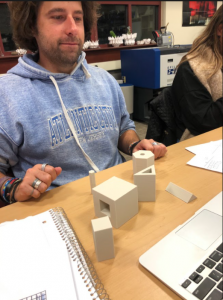

WHAT HE MADE

In investigating this goal during the second interview, David realizes Vincent can already tessellate the floor with like and unlike shapes. This prompts David to change his design path away from tessellations, seeking out the TE after the interview to brainstorm. Still honoring Vincent’s love for shapes, they settle on designing triangular, square, and hexagonal prisms with holes and correspondingly shaped inserts intended to create a one-to-one matching task (e.g., which of these shapes fit together?). During a subsequent design session, David notices that multiple printed inserts do not fit into their intended holes. The TE takes advantage of this moment of struggle to support David through his technological anxieties, and recommends including the extra “mis-shapes” in the matching task (e.g., which of the multiple hexagonal inserts can fit into the hexagonal hole?). David reflects on this being a “teachable moment” as his “mis-shapes” can become usable for Vincent’s learning.

WHAT HE SAID

David embraced mistakes as an important part of his learning and celebrated Vincent’s mathematical discoveries, writing:

“Throughout the process of creating my design, I had made numerous changes. Some changes were logistical while others were tweaked based on my interview questions and responses Victor provided. These experiences have helped shape my understanding of mathematics and how learning happens. I have a better understanding of just how versatile mathematics is and that some of the best tasks and learning take place when [an unexpected] problem presents itself.”

For more, Click here (PDF)

WHAT THIS TELLS US

Our study speaks to the inclusivity that caring brings to learning. Vincent, a member of the students with disabilities (SWD) community, approached and demonstrated learning with animated physical enthusiasm. In a typical mathematics classroom, he might be considered a “disturbance” and subjected to repetitive, rote, and explicit instruction (Lambert, 2015). Instead, the TE and David’s caring-centered pedagogies supported opportunities to embrace Vincent’s inclination to learn with his body, and explore open-ended mathematical ideas together. The TE and David cared for and supported each other through technological apprehensions, even recognizing that design “mis-shapes” could become viable learning tools for Vincent, which helped to dissolve their feelings of exclusion from the Maker culture as their attention turned to care.

Erin's Fraction Orange

HOW SHE STARTED

At the time of her project, Erin was student teaching in a fourth grade special education classroom and wanted to make a manipulative that could help one of her students explore fraction division. She felt that giving her student the opportunity to understand the relationships between a whole and its parts might give him a deeper understanding of what it meant to manipulate fractions (i.e. fraction addition, division, etc.) beyond what he was learning in class. Erin drew on her background in fine arts and took inspiration from everyday objects to quickly decide on creating a fraction orange.

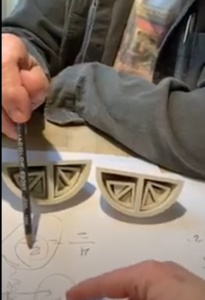

WHAT SHE MADE

Erin’s Making Process was informed by her experience in design and sculpture, so she was able to tackle her somewhat challenging design with relative fluency. She began with a sketch and started “adding” and “subtracting” material and shapes in Tinkercad until she arrived at the fraction orange: a sphere partitioned into two hemispheres, where one hemisphere is further partitioned into fourths, eighths, and sixteenths of the whole, and the other hemisphere is partitioned into sixths and eighteenths. The pieces are nested within each other, which was an important part of the design because it offered the user the possibility of discovering how a whole can be (de)composed into/of parts.

WHAT SHE SAID

“This design experience turned out to be an exciting and inspiring endeavor for me. Much like my fraction orange, it uncovered multiple layers of my understanding of not only fractions, but of learning in general, and how one makes connections between mathematical thinking and concrete experiences. I also learned that both creative design and teaching processes require an incredible amount of thinking and planning, and also tinkering. A design cannot be successful if all the parts of its whole were not thought out…their relationships and interactions must be considered which requires a deep understanding of the material, the making process, and the execution of the design.”

For more, Click here (PDF)

WHAT THIS TELLS US:

This story highlights the importance of fostering opportunities for self-expression through creative acts in the mathematics classroom. Erin found value in having the flexibility to create and bring herself to the work, and she was able to bring her confidence in designing and creating to the class. This turned into a foundation of confidence in doing and teaching mathematics that is vital for any preservice teacher entering the field of education. In addition, her story shows the value in creating opportunities for PMTs to share their ideas and manipulatives with real mathematical learners and doers. During her problem-solving interview, she and her student pursued what he (and it turns out, she!) didn’t know, nurturing genuine and reciprocal inquiry-driven learning. Her sharing experiences via the interviews ended up being truly special and revealing, as Erin and her interviewees struggled to navigate between the traditional approach to fraction division (the “flip and multiply” algorithm) and deeply exploring its meaning with the orange.

WHAT THESE STORIES TELL US: LEARNING THROUGH DOING

So often in schools “the experience of being in the world is subordinated to a mathematical account of that experience” (Dimmel & Milewski, 2019, p. 34) where cultivating a practice of asking and investigating natural questions influenced by one’s environment becomes secondary or even lost. We believe that by creating a physical context grounded in mathematical activity through the design and use of manipulatives, the Maker experience offers students a relief from this disconnect by giving them opportunities to pose authentic and natural mathematical questions. That is, students get to experience mathematics in an environment that acknowledges the fundamental role of their minds and bodies in teaching and learning. As we can see from these PMTs’ journeys, grounding mathematical activity in embodied experiences (like designing, sharing, and using objects to explore mathematical ideas) helps folks to gain deep, lived, and long-lasting understandings of mathematics that far outlive formulas and algorithms, and encourages them to be the mathematical-doers and -knowers that they are. Check out our Project Philosophies Page for more information on embodied learning!